Limit points explained via an analogy

Nathan Kamgang

You’re a girl going abroad for university. A friend tells you: a male classmate from back home will go to the same country. A coincidence, right?

Then you hear he’s in the same city. Closer.

A friend mentions his neighborhood—you tense—he’s moving to the same area.

Finally, you learn from your landlord that you’ll have a roommate. Guess who?

There’s no place for chance anymore. Let the symbol $\epsilon$ represents the distance you look around to check for the presence of your classmate. For every possible $\epsilon$ distance you look around, no matter how small, that stalker is always there. When $\epsilon$ was the size of a country, the classmate was there. $\epsilon$ became a city, a neighborhood, even as small as a house. But you could always find that stalker around. A limit point of a set behaves almost exactly like your situation with this classmate.

$$ x \text{ is a limit point of } A \iff \text{ for all } \varepsilon > 0, \ \text{ there exists } y \in A \setminus \{x\} \text{ such that } |y - x| < \varepsilon. $$

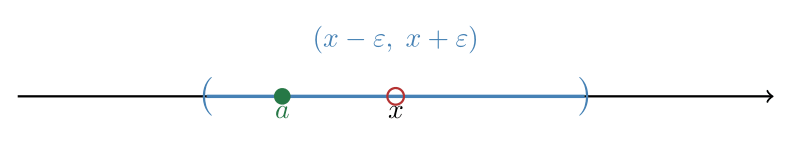

Figure 1: An $\epsilon$-neighborhood around point $x$. Point $x$ itself is excluded, but other points like point $a$ from set $A$ lie arbitrarily close to $x$.

A neighborhood of $x$ refers to the distance around $x$. That distance is of size $\epsilon$. Being a limit point means: no matter how tiny the neighborhood you pick around $x$, there’s always someone from the set $A$ (the classmate) inside it, except possibly $x$ itself (hence $A \setminus \{x\}$).

When we consider the elements from $A$ that are within $\epsilon$ distance from a limit point $x$, we exclude $x$ via the condition $A \setminus \{x\}$. Why? Because a point $x$ is always at distance zero from itself: $|x - x| = 0 < \varepsilon$. If we don’t exclude $x$ from the element of $A$ that should be in the neighborhood, we have that every point in the set could trivially be considered a limit point. The definition requires that there are other points arbitrarily close to $x$, not just $x$ itself.